Written by Mikaila Thurgood

Image: Bruna Grimaldi vineyards in Piedmont, Italy, after suffering hail damage on 6 July, 2023.

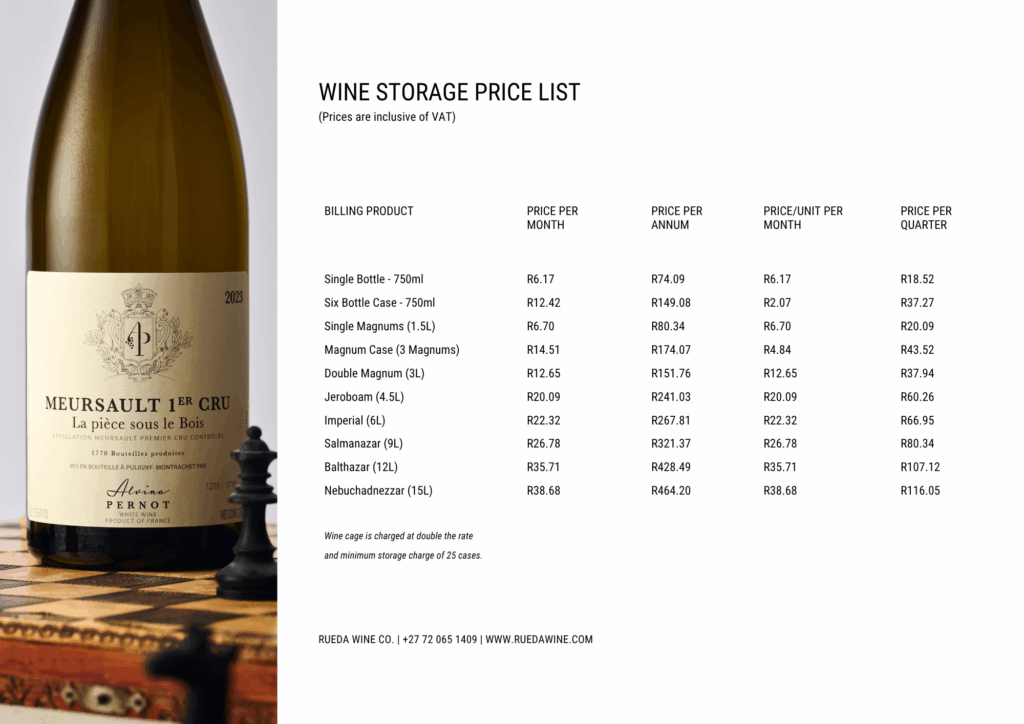

Climate change events are dominating news headlines – from wildfires and droughts to dramatic rainfall and golf-ball-sized hail. These often catastrophic weather events ravage ecosystems, leaving agricultural industries and ecosystems reeling. Agriculture is highly susceptible to climate change. Seasonality disruptions like fluctuations in temperature and erratic precipitation are often disastrous. No agricultural sector is exempt from these impacts, especially viticulture and wine production.

Floods have impacted over 30 million people in Pakistan, scorching temperatures hit Japan, and uncontrollable wildfires are becoming harder to prevent. The hottest month recorded by NASA since 1880 was July 2023. The second hottest month on record was August 2023. This is our reality. But, our reality is also one of growing climate activism, legislation, and government intervention. The world of viticulture is learning to adapt and survive in this ever-changing world.

Climate change places particular pressure on viticulture. Water availability and the threat of wildfires can destroy vineyards, ecosystem and vintages. Likewise, temperature fluctuations from heat waves to sudden frost wreak havoc on a harvest.

Vintners across the globe are trialling methods to reduce this environmental impact. Their methods include agroforestry, artificial intelligence, and experimenting with new grape varieties. And yes, geese are helping in the fight against climate change, too.

Why Is Viticulture So Susceptible to Climate Change?

Quality, wine-producing regions are often found in narrow geographic niches. This puts them “at greater risk from both short-term climate variability and longer-term climate change than other more broadacre crops,” according to a paper presented at the Climate and Viticulture Congress in Stuttgart. Successfully producing a quality wine depends on predictable temperatures with manageable variances. For example, Cabernet Sauvignon prefers warmer climates and a growing season between 16.5°C and 19.5°C. As global warming intensifies, growing seasons become more erratic. Grapes preferring cooler temperatures will begin to struggle for viability alongside their warmer climate counterparts.

This ‘temperature pressure’ is on top of sudden severe weather events. Water scarcity is another pressing concern, especially for independent producers farming smaller areas.

These external climate factors can put significant pressure on winemakers. However, wine production contributes to climate change to some degree. Wine production requires fuel burning during harvest and manufactured glass bottles. These two activities release the most CO2 emissions in the wine lifecycle.

So, what impact does climate change have on wine, and what methods can be employed to mitigate them? How can winemakers look to reduce the effects of their activities? What options are available to alleviate environmental pressures?

How Does Climate Change Impact Wine Production?

Increasing Temperatures and Temperature Fluctuations

“Vines are one of the most weather-sensitive of all crops,” acknowledges wine writer Chris Losh. Temperature fluctuations impact everything from acidity, alcohol levels, tannins, aromas, and more. These variances make it difficult to create the right ‘palatable’ balance. It also means unpredictable harvests. The knock-on effects continue to bottling and export operations.

Losh further explains the impact of sudden, severe temperature drops. In France during the winter of 2021, there were significant temperature fluctuations. These temperature drops killed the vulnerable young vines. The lost vines resulted in a total wine harvest that was the “lowest since the Second World War”. A few years prior, in 2017, an unexpected frost wiped out as much as 40% of Bordeaux’s harvest.

These two examples illustrate the far-reaching agricultural and economic consequences of climate change. Now, when temperatures drop unexpectedly, as they did in 2021, winemakers take action. Some light candles. This heat helps prevent the air around the vines from freezing and damaging the growing buds. However, protecting vines by candle comes at a severe cost. Estimates from Le Tasting Room put the price at €2 500 to protect just one hectare of vines for three nights.

Depending on the size of the vineyard, these costs can quickly become unsustainable. Planning for these changes is challenging due to increasingly unpredictable weather patterns. Vineyards may get repeated days of unexpected frost or be hit randomly throughout the growing season. The lack of predictability also means anticipating unforeseen wine production costs.

Moreover, there is the threat of global warming’s gradual increases in temperature. Warmer temperatures impact grape maturity and the viability of vines in general. Researchers at the Global Conference on Global Warming have forecast the global growing season may warm by an additional 2.0-4.5°C by the year 2100. Below, you can see the ideal grapevine-growing climates for various varieties. Dramatic changes in these temperature bands could mean “higher sugar ripeness…acidity lost through respiration…and higher alcohol levels”. None of these changes are conducive to getting bottles on shelves. They are even less conducive to getting the bottles to hands of wine drinkers.

Image: Gregory V. Jones, “Climate Change- Observations, Projections, and General Implications for Viticulture and Wine Production “, presented at Climate and Viticulture Congress, Zaratoga (E), 10th – 14th April 2007.

There are methods to combat rising temperatures, one of which is the use of shade nets. Nets can reduce the exposure of grapes to harmful UVA and UVB light. Nets also have the added benefit of aiding in moisture retention. Another method uses a white clay called kaolin. This method is reported to have “a positive impact on leaf cooling, minimising the scorching of leaves and clusters during the hottest summer days”. These methods are effective for interim results, but are not long-term solution. Luckily, winemakers have their eyes on the thermometer and are actioning more sustainable, long-term solutions. Some of these include training vines higher, and carefully positioning canopy growth.

Smoke Taint From Wildfires

More than ever before, wildfires continue to dominate global newsfeeds. Unfortunately, many of these fires are taking place in wine-producing Mediterranean countries. These uncontrolled wildfires have the power to raise an entire vintage in an instant. However, the surviving vines are also at risk of smoke taint.

Volatile compounds in smoke are easily absorbed through the skins of ripening grapes. These “accumulate where they become bound to sugars to form non-volatile compounds called phenolic diglycosides”, says the Australian Wine Research Institute.

In bound form, these phenolic diglycosides don’t pose much of a threat to the integrity of the wine. However, enzymes can release free phenols during the wine production process or when interacting with bacteria present in saliva. The result is an overly smoky, ashy or burnt flavour – none of which is palatable.

Aspects such as length of vine exposure and growth stage all impact the severity of smoke taint according to the Institute. Senior research scientist at the Institute, Dr Mango Parker, found grapes can be susceptible to smoke “regardless of size or level of maturity”. What does seem to govern taint impact is the variety of grape. Red wines are often more vulnerable to this taint than their white counterparts.

Between 2019 and 2020, Australia experienced a devastating bushfire season. These fires had a massive impact on vineyards. Some were entirely destroyed by the flames. Others, however, were severely impacted by smoke taint. ABC News reported an estimated “$665 million worth of production and wine revenue was lost” to both vine damage and smoke taint. Napa Valley in California was also impacted by wildfires in 2020.

There are some preventative measures farmers can take to reduce their fire and smoke risks. The starting point is working to prevent the risk of wildfires occurring. However, there are more active strategies that farmers can take. Farmers can work at the vineyard level to reduce the impact of smoke taint. There are also post-wine production amelioration techniques that can be deployed. The International Viticulture & Enology Society has mapped these strategies and summarised them below:

Image: Ysadora A. Mirabelli-Montan et al., “Techniques for Mitigating the Effects of Smoke Taint While Maintaining Quality in Wine Production: A Review” (Molecules, 2021).

New research at the University of Adelaide has also explored using activated carbon hoods. These hoods are placed around the grapes to trap smoke particles. This hood looks like a fabric bag wrapped around the grape clusters and secured at the top. During trials, these hoods protected grapes from 97% of smoke taint.

Water Scarcity

Severe drought and water scarcity are causing viable vineyard areas to shrink globally. In Argentina, water scarcity saw a decline in vineyard surface area of 2% between 2021 and 2022. South Africa has seen a reduction in vineyard size for eight years in a row since 2015 due to severe droughts. In 2019, South Africa was knocked again by critical water shortages in the Western Cape, its largest wine region.

Many vines need to ‘struggle’ for water to produce quality grapes. During this ‘struggle’, vines dedicate energy to the grapes rather than their leaves. This ensures seed dissemination by attracting wildlife like birds. Too little water, however, can limit leaf growth and fruit yield. Vines may also experience premature leaf drop and shoot stunting says Kathryn Carter from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. The harvested grapes from these crops will be nutritionally compromised.

As water scarcity increases, traditional irrigation becomes less and less sustainable. Already, 80% of the world’s fresh water is used to irrigate crops of which viticulture forms a part. Spain, which has one of the world’s largest vineyard areas, is feeling the impact of water scarcity. Due to climate change, Spain saw an increase in irrigation from 36% in 2014 to 40% in 2019. Irrigation is seen as essential solution the face of water scarcity to “assure yields and quality” according to a Vine and Wine Technical Review. It is clear that more sustainable, longer-term solutions are needed. This is especially true amid growing regulatory pressure and restrictions on water use.

Christina Botha, the Head of Marketing and Communication at Rueda Wine Co. recently spoke to Sakkie Mouton, a winemaker who grew up and now farms along the West Coast of South Africa. This region was put under particular pressure during the recent droughts. Mouton has since deployed prudent farming techniques and said, “I’ve had to sucker the vineyards a lot, and I try to thin the crop to fit the season. That’s all on feeling, there isn’t a scientific way I do it”. However, sometimes active water management strategies are needed.

There are a few ways to combat water scarcity. The mode of irrigating vineyards is the first line of defence to conserving water. Some farmers might move from surface irrigation to more efficient drip irrigation, while some methods involve using reclaimed irrigation water and rainwater tanks. Farmers also have the option of using more drought-tolerant rootstocks to help their crops survive. There are also ways of reducing soil water evaporation through mulching and canopy management.

Vineyard water management solutions will require input from many stakeholders. Researchers are considering grapevine ecophysiology and genetics, crop and water use modelling solutions. Regulatory partners are working on best practice principles and policy recommendations. This knowledge, when combined, can be a powerful tool for combatting climate change.

The Risk of Floods

While water scarcity can damage vines, excess water can be equally devastating. In March 2023 New Zealand floods covered vineyards in tons of mud, weeks before harvest. In May, the Emilia-Romagna wine region suffered €10bn in damages when 20 rivers flooded. Flooding has become a devastating problem for wine production globally, and in South Africa.

In South Africa, winemaker Sakkie Mouton experienced first-hand the impact of flooded vineyards. Mouton’s Columbar, growing next to a river, takes its name Vloedvlak (“flood level” in Afrikaans) from the methods used to irrigate the old vines. In June earlier this year, the area experienced its first flood in over sixteen years. The Oliefants River burst its banks and left Mouton’s vines submerged. “In Lutzville, there’s a rock that gets marked every time it floods, and 1925 was the last time it was as high as this year”, remarked Mouton in a conversation with Christina.

Image: Published by Greg Sherwood, September 2022, depicts Sakkie Mouton’s Old Vine Colombard, planted in 1978.

Image: Provided by Sakkie Mouton depicting the results of the June 2023 floods on the Old Vine Colombard vineyard.

Luckily Mouton’s vines had not yet budded. However, as wet weather persisted in the Western Cape, the area flooded a second time in August. “The first time it wasn’t a bad thing, but the vineyards have started budding…When I left the farm yesterday the water had started pushing in at the legs of the vineyard, if it rains through the weekend they will be covered”. The area saw some respite during the weekend that followed, and the water levels subsided.

This moment speaks to the uncertainty that many winemakers face confronting climate change. As global temperatures rise, the frequency of flooding and other extreme weather events is modelled to increase. There are, however, always new solutions created by innovation and research. Many vintners are also championing the cause for change and searching for new answers.

What Can Wine-Producing Regions and Makers Do to Mitigate Climate Change?

Taking Advantage of Agroforestry

Just as wine production is impacted by climate change, it is also a contributor. As much as 23% of the world’s greenhouse gasses are emitted by agriculture, forestry, and land use activities. One way of mitigating and protecting against climate change is through agroforestry.

Agroforestry is a climate-change-mitigating land management approach. This approach incorporates trees, hedges, other crops, and livestock into an agricultural area. For winemakers, planting trees among the vineyards promotes healthy bio-diversity. These trees provide a habitat for animals and more organic material for the vineyard. Birds also act as natural pesticides in vineyards. In a study from the University of Perugia, geese, in particular, help reduce copper levels in soil simply by grazing among the vines. Excess copper (usually used to ward off fungal diseases in vines) can lead to impaired wine quality and tissue damage.

Additionally, agroforestry can help create microclimates with lower mean air temperatures. This can be a crucial environmental factor for low-temperature wine varieties. It also helps produce shade for grapes, draws water from deeper soil layers, and creates vine windbreaks. These agroforestry barriers can offer vineyards more protection against extreme weather events. Through carbon and nutrient cycling in soil, agroforestry can improve soil fertility and reduce erosion.

There are examples of vineyards around the world using agroforestry to combat climate change. They work to preserve significant biodiversity habitats and reduce reliance on pesticides and fertiliser.

- California-based Benziger Family Winery is Biodynamic Certified, uses natural pest control and has This farm uses natural pest control and has “constructed wetlands that filter water and offer habitat for a multitude of species”.

- The only Biodynamic Certified wine farm in South Africa is Renyeke in Stellenbosch. Reyneke is “herbicide, pesticide and fungicide free”. They use companion plants to break up compacted soil and absorb nitrogen from the atmosphere. In the vineyards, natural predators such as ducks roam freely to catch pests and fertilise the soil.

- Australia’s Yalumba winery was one of the first to be certified carbon neutral in 2011. This winery focuses on biodiversity, soil health, and water conservation methods. One method includes rainwater harvesting to produce more sustainable wines.

Finding Protection by Planting Different Grape Varieties

There is an opportunity to ensure the longevity of wine production despite climate pressures. This strategy relies on using more heat- and drought-resistant grape varieties. Research at the University of British Columbia has found that different varieties – such as Pinot Noir are less resistant to more heat-tolerant varieties such as Syrah and Grenache.

In Austria, winemakers have begun experimenting with the late-ripening Furmint variety. This has led to cultivation areas tripling in the last eight years. In California, winemakers are experimenting with more heat-loving grapes like Aglianico and Syrah to combat prolonged heat events. Spanish grapes like Palomino Fino, which thrive in warmer climates, are also used in Australia. South Africa is also testing drought-resistant varieties, including Assyrtiko and Marselan. “The cultivars I work with, for example, Colombard, Chenin, and Vermentino can pretty much handle drought to a certain extent”, commented Sakkie Mouton who has chosen his cultivars to survive in drier conditions.

Artificial Intelligence and Wine

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is everywhere, and for many winemakers struggling with growing climate uncertainty, this could come as a relief. One benefit of adopting AI is wielding the power of prediction. Californian company Tule, combines AI and agronomic analysis. This data can provide growers with insight and irrigation decision support. Sensors are placed among vineyards which measure vital metrics. They measure evaporation levels from soil, plant surfaces, and transpiration from plant leaves. The benefits? A timeous, accurate view of how much water vineyards are using and a gauge of water stress levels.

Winemakers now have a lot more information at their fingertips. Technologies like wireless soil sensor networks and drone technology help provide critical information. These technologies allow growers to directly monitor vine health. Growers can also determine the impact of recent weather and take decisive action. This data then comes together in comprehensive and catalogued cloud databases. Growers are then able to make better, more sustainable winemaking decisions.

As this technology continues to evolve, greater benefits and uses will be discovered. This change marks a significant moment in history. One where farming methods, weather, and cutting-edge technology begin to shape the future.

Breaking New Ground: Making Wine in Places Previously Thought Impossible

As climate concerns ramp up for vintners, their livelihoods are put under pressure. Understandably there is a trend to look north to cooler climate ecosystems. These cooler climates can offer vintners a safer and more hospitable vineyard area.

Hotter summer temperatures in Europe are moving harvesting times forward. Previously “inhospitable” climates like the United Kingdom, Germany, and even Sweden are becoming popular regions for new vineyards. In South Africa, Sakkie Mouton farms Chenin in a town called Koekenaap. This is the same area that was previously not climactically viable 30 years ago. Planting new vineyards or moving to new soils is one solution. However, there are still many environmental and winemaking impacts to consider.

As more viable vineyard areas are identified, winemakers are looking to move north. Cropping patterns will also therefore naturally shift. According to 2020 research, this could have a significant impact on, “water, wildlife, pollinator interaction, carbon storage and nature conservation, on national to global scales”. These newly suitable areas are titled “Climate-Driven Agricultural Frontiers” by this same article. The area is equivalent to 30% of the current agricultural land on the planet. Simply taking advantage of these frontiers is not the straightforward solution. Without considering the long-term consequences, the environmental impact could be dire.

Winemakers, like Ian Naudé, work hard to capture the quintessential elements of the land and reflect them in his wines. “I go and I try to find what grapes work in that terroir, to be able to take a liquid photo and put it in a bottle – but to do this you need to work with respect”, noted Naudé. The balance of respect for the land and new possibilities will be essential for the future of winemaking.

Winemakers will need to find sustainable practices when expanding vineyards, agricultural practices, and wine production methods. The right climate-change-mitigating techniques might be the only way to protect their future. This will be true whether winemakers are headed north, south, or driving their roots deeper into home soil.

Written By: Mikaila Thurgood

Contributing Writer: Christina Botha

Fact Checked By: Mikaila Thurgood and Christina Botha

Edited By: Fernando Rueda