Chardonnay is a grape of contradictions. Used in mass-produced wines, Chardonnay occupies a contradictory space. It is prominent among elite producers and near the top of many fine wine lists. It even occasionally appears as the most expensive wine out of Burgundy, one of the world’s dominant wine regions. Add to this its reputation as a middling varietal that’s often flat and mediocre. One may wonder why it occupies its place of importance in the wine world. While it’s true a ‘bad’ Chardonnay can be tepid, even dreary, its stunning versatility and response to various winemaking techniques allow winemakers to nurture a wine that ranges from a high-acid, high-minerality haymaker to a delicate, lightly-aromatic medley of notes.

Chardonnay the Grape

Image: The Batard-Montrachet vineyards of Pierre-Vincent Girardin planted to Chardonnay

While not unique in claiming a wide range of siblings, Chardonnay is related to Gamay Noir, Aligote, Melon Blanc, and Riesling. Researchers have determined a direct parental link between Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. It has over a hundred synonyms, most of which are no longer in use except for its regional appellations. Named after the commune Chardonnay in the Maconnais.

Chardonnay grapes are exceedingly adaptable to climate, topography, soil, sun exposure, and terroir, so we find it worldwide. From mass-produced wine to artisanal revelations, it graces the cellars of many winemakers who revere it as art. Some of the mass-produced Chardonnays have perjured the reputation of the variety. But given how it succeeds and responds in every climate from cool to very hot, there are examples of great Chardonnays in almost all of the forty or more countries that cultivate it.

It’s early budding, so it suffers spring frost in Burgundy, Champagne, and Jura. But it’s also early ripening, so there is a decent yield, meaning it produces a larger crop per land unit in the vineyard. Due to this yield, Chardonnay tends to be lighter on flavours; the more grapes a vine produces, the fewer sugars develop. To make the grape more flavourful, the farmer can curtail the vigour. Beyond the soil and the vine care, temperature and sunlight are the next factors that determine the health and quality of the grapes. Chardonnay finds its greatest challenge in the cold winters of its ancestral home of Burgundy.

Burgundy

Image: A view over Domaine Vincent Dancer’s Chevalier-Montrachet vineyard in autumn as the leaves turn gold.

Chardonnay likely originates from Burgundy, Jura, and Champagne. The grape dates back to the 17th century, but has probably existed in the region since long before. Earth’s most widely planted white grape is Chardonnay, over 225 thousand hectares are under vine worldwide.

The Cote d’Or, in Burgundy, is named for the gilded hue of the vineyards in autumn. It comprises the main town of Beaune and the city of Dijon. Beaune is Burgundy’s wine capital and the most famous settlement for wine production. Burgundy’s southeastern orientation on a limestone cliff has resulted in extraordinary terroirs.

Image: One of the crowning landmarks of Beaune is the Hospice de Beaune.

The Romans conquered Burgundy around 50 BC and are credited with formalising winemaking in the region. However, the Christian monks changed the way wine was made. Their focus on improving quality and developing new techniques elevated viniculture. The Cistercians were the first to make Chablis. The Cenobitic monks of Jura focussed on serving the broader community, including through winemaking. The Benedictines were the first great generalist winemakers of Burgundy. They stratified lands and terroirs to try to make even better wines. The idea of ‘pursuing the perfect ground for the perfect grape’ informed Burgundy’s appellation system and many of the vineyards started by these monks remain some of the region’s most famous.

Image: General characteristics of when tasting Chardonnay from around the world.

Burgundy’s appellation system, Regional, Village, Premier Cru, and Grand Cru signifies the quality of the grapes, the terroir, and the resulting wine. There are only 33 Grand Cru sites in the whole of Burgundy. Pinot Noir and Chardonnay are the only varietals here. These vineyards have fewer hectares than almost anywhere else in the world and a codified restriction on the number of vines permitted in each hectare. As such, the yields are very low, even extremely low, among the older vines used for Premier and Grand Cru. Many Chardonnay producers in Burgundy use oak barrels for ageing that are 228L. Barrel-ageing sees the winemaker using a distinct barrel shape that is shorter and wider and differs from the slimmer profile of Bordeaux barrels. This affects the amount of contact the wine makes with the vessel.

Many of the Burgundian techniques and the region’s focus on wine are due to a historical demand for wine, which the Dukes of Burgundy helped to promote. They supported the monasteries and monks’ pursuits in the art of winemaking in the late Middle Ages.

Bourgogne Techniques

Image: Burgundy barrels in Pierre-Vincent Girardin’s cellar in Meursault.

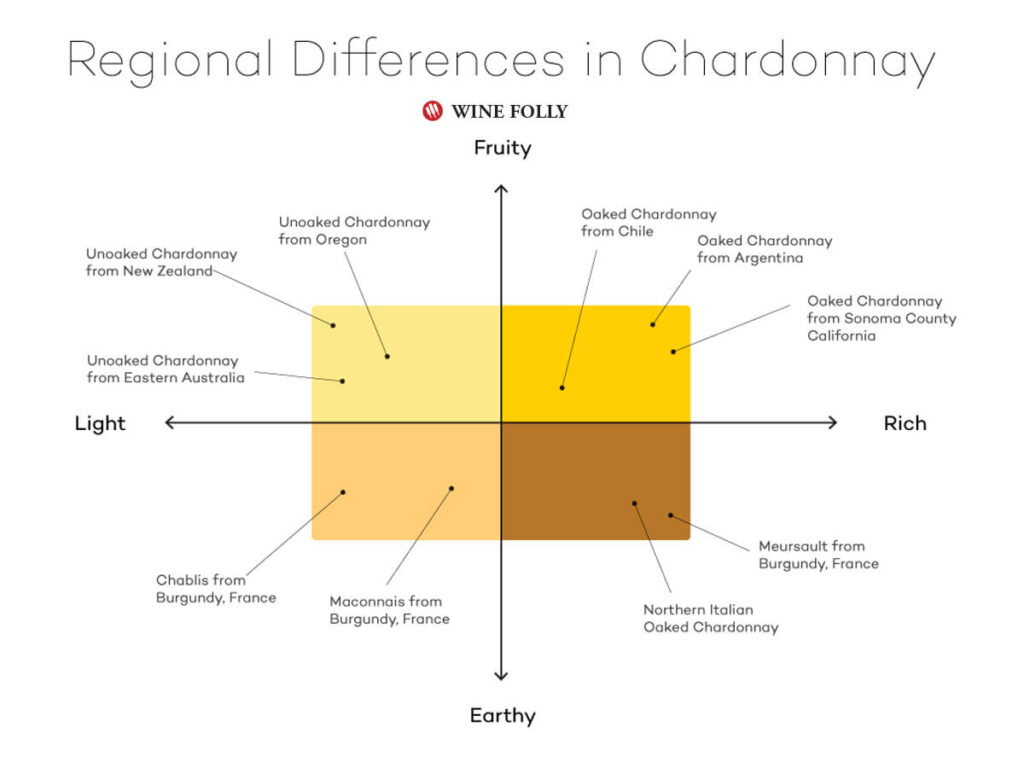

Here, we refer to techniques popularised in Burgundy and adopted by winemakers worldwide. Wooded or unwooded (or oaked or unoaked) is the most well-known difference in Chardonnay ageing methods. New World wine regions almost always indicate this on their labels. It indicates whether the Chardonnay has been aged in wood or not. Unwooded Chardonnays tend to be drier and have higher acid, whereas wooded Chardonnays have more complex flavours like vanilla, oak, bread, toast, or even smoke. Furthermore, oaking softens the wine.

Typically, these Bourgogne Chardonnays are medium acid, mid-bodied, often radiantly gold, and though they’re oaked, they aren’t subsumed by it. They tend to be dryer, containing very low amounts of sugar. The wine is semi-aromatic, which means that it needs help to compile sophistication. The type of barrelling, fermentation, and winemaking techniques used here are important, though the smaller barrel ageing and greater contact with the wood, which enhances flavour, is one of the primary factors in elevating Bourgogne Chardonnays. The grape is very sensitive and sometimes exhibits the region’s striking limestone soil more than itself.

Because of how Chardonnay responds to interventions, it lends itself to many winemaking techniques. Whether the winemaker decides to destem, utilise cultured yeast, prolong maceration, or rack multiple times all affect the final product. Some producers destem the grapes, but whole bunch can impart more structure to the wine. However, this carries the risk of contaminating the must.

Image: Stirring lees during the ageing process at Frank Family Vineyards.

Malolactic fermentation is a process in which malic acid turns into lactic acid with the introduction of bacteria. Lactic acid is softer; think yoghurt. Malic acid is harsher; think unripe apple. Softening the wine makes it less lean or tight and rounds out the style. Battonage, the French term for barrel stirring, creates a more buttery texture. This is achieved by stirring the lees – sediment, dead yeast or other residue that collects at the bottom of the barrel – back into the wine, creating a very specific flavour profile.

‘Ageing on the lees’ keeps leftover sediment in the wine after fermentation. This can be risky as it allows more flavour profiles to develop but does not prevent the introduction of undesirable flavours. A winemaker might use this technique to impart more of the nuttier, baked, and straw flavours they seek. Racking, the process of moving wine by gravity, siphons the wine off the yeast (and other unwanted matter) and allows for clarification. As opposed to the previous techniques, the winemaker separates the wine from the yeast and plant matter to slow the conveyance of yeasty notes. It may help the wine retain some natural sweetness as well. The highest quality Chardonnays almost unanimously follow the Burgundian model of maturation in small barrels. This delivers the expected creaminess and hazelnut flavours as secondary characters.

Keeping the wine in contact with lees during fermentation is another way to mitigate acidity and can impart flavour and texture. Chardonnay is often matured in oak barrels, adding complexity through oxidisation and imparting ‘oakey’ flavour characteristics: the buttery, vanilla, and caramel notes the varietal is famous for. Over-oaking and employing too many winemaking techniques can be risky because Chardonnay doesn’t have a depth of aromatics to sustain through too many processes. Conversely, Chardonnay that isn’t safeguarded during fermentation may be susceptible to too much oxidation, resulting in Chardonnays that taste closer to sherry and other fortified wines. For Chardonnays that struggle to display leanness and elegance, sulphur can be used in the vineyard and sprayed into bottles and wine must. This free sulphur dioxide in the wine further imparts notes of minerality.

Macon: A Burgundian Town against the Grain

To sample a Chardonnay that is fairly unique among the Burgundy producers, one should look for something from the Macconais region. Here, they opt to focus on the clean, crisp taste of fruit while highlighting the delicate aromatics. They rely on the chalk, limestone, and flint geology to impart mineral notes to the wines. Macconais Chardonnays tend to be very dry and loaded with crisp fruit notes, making for a fresh and wiry wine.

Chardonnay Clones

Chardonnay is likely the most clonally diverse grape used in modern winemaking. Several of the more than a hundred Chardonnay clones grown today have been selected for their yields, depth of flavour, or resistance to certain diseases. Different clones have different root formations, durability, and mineral and water utilisation. Some of these clones excel at showcasing mineral, flint, and stone characters, thereby making them the perfect canvas for a particular terroir. And even more, excel at expressing specific fruit types in the bottle.

Certain clones have been further enhanced for styles. If producing sparkling Chardonnays as they do in Italy, one may consider using Chardonnay 18. While Chardonnay 76 and 95 are found all across Burgundy, they can also be found in South Africa. These clones are organically lower yield and may explain why the Burgundian grapes produce such complex and flavourful Chardonnays.

A Worldwide Darling

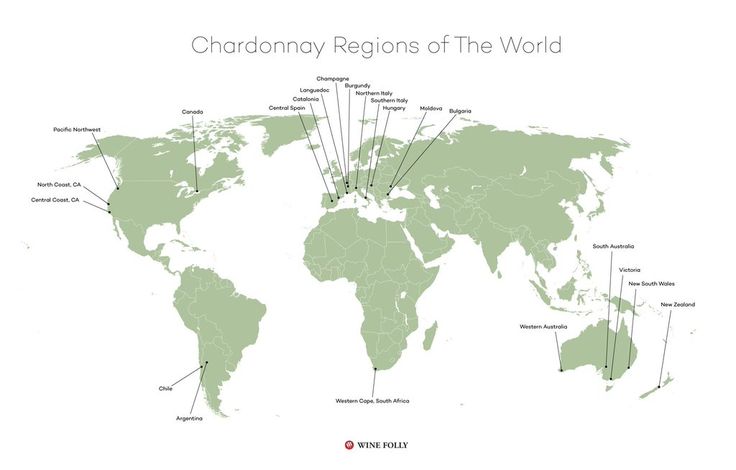

France may be the top producer by volume, but Chardonnay is famous everywhere, especially in America, Australia, and Italy. These last three round out the list of Chardonnay’s top four producers. However, the Big Four Chardonnay regions are responsible for only half the worldwide volume. South Africa, Germany, Austria, Chile, Argentina, Canada and New Zealand all have interesting examples of Chardonnay. We’ve considered the Bourgogne cold climates notes: green fruits, vanilla, oak, bread, toast, and lemon peel, so what does it look like in hotter climates?

Image: Chardonnay plantings throughout the world.

Firstly, fruits in warmer areas develop higher sugar levels than in cooler areas and are, therefore, lower in acid. This means many fermentation and ageing interventions practised in Burgundy aren’t strictly required. It is commonly aged in oak barrels in South Africa, America, and Australia and allowed to undergo Malolactic Fermentation. The majority of these Chardonnays are buttery, rich, and sumptuous.

Oak chips are added to simulate some of the barrel ageing effects in mass-produced wines. This is generally an inferior method, which results in lower-quality wines. True barrel ageing develops structure. This balances the fruit notes and aromas, acidity, sugar, and alcohol levels. The American style of using new oak adds even more body than older barrels, making Chardonnays bold and oily. A well-aged Chardonnay should be creamier, have medium acidity, and tend to have nuttier flavours as it matures.

Hot climate Chardonnays tend to express more tropical fruit notes like orange, melon, and pineapple. However, the lower acid content is a double-edged sword. Though more citrusy than colder climate Chardonnays, it can be flatter and lack a crescendo in its finish. It’s a balancing act for winemakers to elevate their Chardonnay, permitting it to sing on the palate.

Climate Change and Chardonnay

As previously stated, Chadonnay’s ubiquitous planting injured its reputation, but its resurgence in esteem is well earned. It’s an international varietal, significant in most regions where it is planted. Because of its easy growth and neutrality, it’s one of the best wines to showcase terroir.

But Chardonnay’s responsiveness to temperature is both a blessing and a curse. Its weakness to spring frost in Burgundy means that as temperatures change, more and more technological and manual interventions are required to protect budding grapes from frost. Conversely, when the grapes get too hot, it impacts the development of sugars, inhibits the maturation of the fruit, and can affect the colour of the juice and the aromatics. Even worse, it opens the vine up to diseases, which Chardonnay is acutely susceptible to.

Image: Farmers in Burgundy fighting frost with candles.

Chardonnay’s thin skin makes it a breeding ground for Botrytis and many types of mildew. Worse still, many of these diseases curtail acid or cause the grape to overproduce sugars. This renders the grapes unsuitable for winemaking. Chardonnay is difficult to use in sweet wines as it doesn’t have the high-acid, high-aromatic qualities of varieties like Chenin Blanc. If temperatures continue to rise, we may see a shortage of the fresh, minerally, and delicate colder clime Chardonnays. Regions already on the border of being too hot will see their yields plummet as they fall prey to disease and flat-tasting grapes.

Champions among Chardonnay: Jura

While we’ve discussed how almost every wine region has outstanding examples of Chardonnay, some stand out even among the best Chardonnays in the world.

From Jura, the Domain Fumey-Chatelain Chardonnay is a profoundly important wine that expresses everything wine connoisseurs love about the Jura Region. Aged for one and a half years, it pirouettes between the central tension of Chardonnay, delivering both freshness and body. They are famous for their oxidative wine style, which reveals a rarified complexity.

Champions among Chardonnay: Burgundy

Burgundy has no shortage of incredible producers, with many winning worldwide accolades and others enjoying status as dynastic titans of the wine world. No list could be exhaustive, but here are some of the many that we’ve had the privilege to work with.

Pierre-Vincent Girardin (PVG) is a lauded Meursault producer, delivering several Chardonnays of note with a handful of 1er Cru and Grand Cru sites. The Eclat De Calcaire Chardonnay manages, like few of even the greatest Chardonnays, to deliver aromatics and a buttery body. Unique among Bourgognes for using barrels twice the size of the standard Barrique (456 litre), PVG imparts the best oaking attributes while retaining the delicate flavours cherished among colder climate Chardonnays.

Image: Pierre-Vincent Girardin Standing in his vineyards.

For Genot-Boulanger, terroir informs everything they do. They believe their charge as winemakers is to be as “discreet as possible to let our terroirs express themselves and transcribe all the qualities of our wonderful Burgundian climates.” The 100% Chardonnay Genot Boulanger Beaune En Lulunne Blanc 2021 saunters between the margins of green stone fruit, expertly taming acids and elevating mineral notes. And all without diminishing the complex fruit that sings earnestly about its home slopes.” – Quote from Genot Boulanger Our Philosophy

The Theo Dancer Roc Breia is a splendidly precise wine. It’s another example of Macon’s tradition, and under the Roc Breia label, Theo Dancer, a generational talent, can investigate new methods and techniques.

“Aromas of pear, white flowers, bread dough and hazelnuts, followed by a medium to full-bodied, fleshy palate with a satiny attack that segues into a charming, lively mid-palate, with good cut and a saline finish.” – RWC’s tasting notes

Champions among Chardonnay: Champagne

Sparkling wine production often uses sparkling wine. For those who don’t know, not all sparkling wine is champagne. Unless it is produced there, it can’t be called Champagne. One must present the region’s finest examples to be worthy of the appellation.

Etienne Calsac is a master of Chardonnay. The Champagne Etienne Calsac L’echappee Belle NV is a sparkling wine that every wine lover should have the opportunity to try. Etienne Calsac started by leasing vines but cemented his position as an expert winemaker and a Champagne producer of rapidly rising renown. Expect sour lemon before embarking upon a voyage with crisp green fruit and a repeating finish that evokes freshly baked bread. Clear and brilliantly gold, it epitomises the Champagne Terroir.

Image: Etienne Calsac working in his winery.

La Rogerie’s Champagne La Rogerie Heroïne Grand Cru is an example of the zenith of the appellation hierarchy. One of less than forty Grand Cru Champagne villages, it claims the most rarefied company in the wine world. Hailing from Avize, Champagne, the La Rogerie label is synonymous with outstanding quality.

“Complex, savoury, freshly grated apple peel, cumin, straw and mallow, very subtle yeast influence. In the mouth, vinous, medium-fine mousse, firm acidity, slight sweetness, and textural touch in the transition to the finish, the mineral aspect is restrained and more chalky than savoury. 94/100” – Falstaff

In Leclaire-Thiefaine, we find many Cuvees worthy of notice. The Cuvee 01 Grand Cru d’Avize Blanc de Blancs Extra Brut NV is a triumph of minerality and aromatics, generously swaying between these two poles. Headed by the fifth successive generation, this Avize estate boasts several Grand and Premier Crus. At only three hectares, Leclaire-Thiefaine’s inspirational vines and strict adherence to traditional methods guarantee that one will taste the pinnacle of both the terroir and the appellation.

Champagne Leclaire-Thiefaine Cuvée 03 NV uses some of the oldest vines in Avize. The grapes burst with flavour and the nuance of this nearly 150-year-old estate. Described as “refined and elegant,” the Cuvee 03 perfectly encapsulates the clay-limestone it hails from.

And last, the 92 % Chardonnay Premier Cru, 8 % Pinot Noir Grand Cru, Champagne Leclaire-Thiefaine Cuvée 02 Le Rosé is a wonderfully nuanced champagne that conjures fruits of a more citrus tone. The light blend offers something unique in the flavour profile among colder climate sparkling Chardonnays. Its pinker complexion is a prelude to the refreshment it so generously delivers.

Champions among Chardonnay: South Africa

Inevitable Wines arrives in style on our shortlist. In their 2022 Chardonnay, we find a wine that exalts peach, pear and bright green fruits and hints at fynbos, a unique marker of its singular terroir. Barrel-fermented and barrel-aged for twelve months.

Image: Inevitable Wines’ Chardonnay vineyard in Stellenbosch.

Given Chardonnay’s exceptional knack for showcasing the nuances of the soil and its terroir, it’s best to sample different regional varietals. There are so many varied techniques and styles of Chardonnay, if you don’t love it, you haven’t found the right one for you yet. Enjoy your search.

It will surprise you!

Written By: Rhett Sinnema

Fact Checked By: Fernando Rueda

Edited By: Fernando Rueda