It might be a stretch to claim human civilisation would not exist without wine. However, shifting from hunter-gatherer to farmer required certain advancements in agriculture. It is these advances that were the catalyst for the development of our modern society. The history and evolution of wine in cultures shadow the shifts in economic and cultural influence of countries and regions. Now, in this globalised modern era, trends are shifting. One can see influence and taste-making transfer from world leaders to “peripheral” countries. As seen in our Chenin Blanc deep dive, peripheral (in economic theory) countries like South Africa are now challenging the old guard of Europe. Or, at the very least, successfully demanding their seat at the table of evolving wine techniques and cultures. We explore the odyssey and origins of South African wine.

Fermented Food and Drink 10 000BC – 4 000BC

We’re not entirely sure when humans discovered the inebriating effects of fermented fruit. But ever since humankind’s mode of living changed from nomadic to settler, cultures have been trying to perfect the art of alcohol. As early as 9000 BC, there is evidence of fermented drinks. The earliest grape-based drink was a fruit and rice concoction in China circa 7000 BC.

Various civilisations of antiquity enjoyed beverages resembling wine as we know it today. These were regions such as those now known as Armenia, the Greek Islands, Iran, Sicily, and Italy. Historians believe that societies used wild grapes in the earliest rudimentary winemaking. The oldest facility focused on the production of wine is in Armenia, in Vayots Dzor. Some estimate it to be more than 6000 years old.

Recently, new archaeological discoveries have begun to challenge the euro-centric history of wine. Some historians are now reconsidering China as the first region in the world to make wines at any scale. They also believe it likely they were doing so long before any other region or nation. But, just as wealth, power, and prestige move from nation to nation and region to region, so too has the centre of wine toured the globe.

A joint project of the Georgian National Museum and the University of Toronto also makes claims to the first incidence of true wine. Archaeologists have discovered grape matter and residue in various vessels there. Their conclusion is these were likely used for fermentation or ageing. This is strong evidence that ancient Georgia was the first location of grape-centric fermentation.

Early Civilisations and Antiquity 3900BC-600AD

While the genesis of wine is murkier, the later societies of antiquity have strong records of wine production. Records of winemaking exist in the centres of the world like Persia, Egypt, and Greece. The Roman Empire was also instrumental in spreading wine cultivation and appreciation. They were notably responsible for bringing wine to France during the early expansion of the empire.

As trade goods, wines from imperial powers were highly sought after both for their quality and as status symbols. To this day, France still holds dominance in the wine world, exerting influence because of its pedigree and influencing taste. Many experts consider it likely the best wine humanity has ever produced has been made in France.

But the challenge to French Wine Hegemony is not only from other old-world luminaries like Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, Greece, and Portugal. New world regions like Australia, America, and South Africa are also competitive. In wine, just like any pursuit from enterprise to art, there is always a centre and periphery. The South African wine story and its journey from fringe producer to precocious darling is as intricate as it is enthralling.

1400-1699 Portuguese Explorers, Dutch East India Company, and the Cape of Good Hope

During this period, the world was expanding. Explorers took to their ships to discover the potential riches new lands had to offer. One of the most famous of these explorers was Vasco De Gama. He was the first European explorer to visit South Africa in the 1400s whilst looking for a new route to India. During the 1400s Vasco De Gama and other Portuguese explorers and naval captains merely visited South Africa. It was only in the 1650s that we see the first concrete steps to producing the first South African wine.

It began when the Dutch East India Company, or VOC, established a small trading post in the Cape of Good Hope. They aimed to break the Portuguese stranglehold on East Indian goods. The first governor of the Cape, Jan Van Riebeek, ordered the initial planting of grape vines in 1655. By 1659, the first-ever South African vintage was finally ready.

It must have been impressive or at least laden with potential. Within twenty years of the first vintage, mandates went to farmers to plant vines in small sections on their farms. The next governor of the Cape was Simon Van Der Stel. He was an oenophile responsible for catapulting South African wine to international acclaim. Not only did he found the town of Stellenbosch, a superlative wine region today, but he planted an enormous quantity of vines in Constantia. At the end of the 17th century, Constantia sweet wines had become a phenomenon. They were readily enjoyed by members of the aristocracy (and even the monarchies) of several European nations. Napolean Bonaparte and Marie Antoinette both praised the quality of the Constantia Wines.

The Early Tribulations and Successes of Colony Wine Farms

However, this early success was not indicative of the general experience of farmers among the first colonists. The Dutch East India Company often interfered, applied, and enforced stringent rules. Proscriptive pricing models often devalued the settlers’ produce and wine. Farmers were prohibited from trading with other companies or nations using the trading post. These rules ensured all profits derived from enterprises around the Cape flowed directly to the VOC rather than the farmers.

Unsurprisingly, this strangled the fledgling wine industry and stymied further advancements. However, one should note it was the very sailors, employees, and merchant ships of the company that made up the bulk of the customers for Cape Wine. These VOC rules, however, were not unilaterally accepted. Cornelis van Niekerk, whose family would start Van Niekerk Vintners, was among the first colonists to resist the onerous and anti-competitive laws. They circumvented VOC, selling directly to passing ships. Cornelis and eight other farmers, received the label “The 9 Rebellious Vrijboeren” and endured imprisonment for refusing to bend to the VOC.

Image: The Arms of the Dutch East India Company, Oil on Panel, Jeronimus Becx (III), 1651, superimposed on an old map of the Cape of Good Hope

A Loosening of the Law

There were other deplorable stories from this time. However, it was not long before the colonists began chaffing at VOC law. Looser laws allowed the Cape of Good Hope Trading Post to develop an agricultural industry. This industry started to expand beyond the resupply of the VOC ships. It was only during the 18th century that most of the stalwart grape varietals made their way to South Africa.

Some sources claim these early wines were of very poor quality. It is unclear why the wines were of such a low quality. Some argue it was due to an ignorance of methods, while others a lack of economic incentivisation. However, before the 18th century, Cape wine, if one was feeling charitable, would have been deemed a cottage industry. But, in 1688, with the arrival of French Huguenots, Cape wine would change forever.

The Arrival of French Winemakers and Advanced Techniques

The Huguenots settled in Franschhoek, another of the Cape’s exceptional terroirs. The Huguenots brought sophisticated French techniques to the Cape winemaking practices. These practices included better barreling methods in oak vessels, vine maintenance and manipulation. These techniques helped improve both yields and grape maturity. The Huguenots also introduced stricter and cleaner fermentation methods during the winemaking process. These are just some of the specialised skills introduced into Cape winemaking by the Huguenots.

Compared to the novice farmers, Van Der Stel notwithstanding, the Huguenots were masters. This first technique revolution due to French influence is reminiscent of other modernisations. One can compare this to the winemaking technique revolution that occurred in Barolo and the rest of Europe.

Some scholars challenge this once widely accepted history. These scholars argue that evidence suggests these early Huguenots were not highly skilled winemakers. Although many of them found work on wine farms. Some scholars hold that the 18th-century French settlers introduced the revolutionary French winemaking techniques.

Uncertain timeline disagreements aside, it is clear that the early Cape wine industry was not a vital economic pursuit. While winemakers had adopted new techniques, Cape wines still lacked appeal in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

Furthermore, any excellent wines that Cape winemakers produced were subject to VOC rules. These rules mandated the sale of most, if not all, of the best wines to VOC officers and influential members. Regulations also determined the selling price of Cape wine. Unsurprisingly, the Cape wine industry did not flourish under these artificial market constraints. There are, however, moments in this period when certain Cape vintages broke into the international market.

1700-1910 The British Empire, War, and Plague

The late 17th century and early 18th century war between France and Britain resulted in heavy sanctions on French wines. Some of these tariffs and import protections remained in place for the next hundred years (or more). But Frances’s loss was the Cape’s gain, as they found a new international market for Cape wines in the greater British Empire.

Global Power Dynamics

This fortuitous moment in shifting global power dynamics played into the hands of Cape winemakers. The VOC was also in a state of contraction and was unable to prevent the arrival of the British in the Cape. The VOC, and their market practices, were eventually ousted from their position in Cape of Good Hope. This allowed Cape wines to enjoy a brief time of favour in the first half of the 19th century. While the famous Constantia wines were still desirable, other producers and vintages began to flourish. With some French war tariffs still in place, Cape winemakers quickly increased production. Protected by tariffs, they could attempt to meet the British Empire’s thirst for wine.

The industry multiplied nearly ten times to almost five million litres in only two generations. Unfortunately, many British sanctions on French wine were repealed in 1861. French wine, as the preferred country of origin, was once again traded in most of the British Empire. As a result of this rapid and ruinous shift back to the world leader of wine cultivation, Cape wine production waned. If this market contraction wasn’t catastrophic enough, winemakers suffered another near-death blow. A disease deadly to vines had migrated from Europe and made its way to the Cape.

The Onset of Disease

The Phylloxera Aphid struck the Cape. This infestation unfortunately destroyed millions of grape vines in the Cape. This tiny insect, feeding on roots and leaves, had already decimated much of Europe. Baron Carl von Babo, the Cape Government’s wine expert at the time, made several recommendations and interventions. He advocated for the cessation of European vine importation. When Phylloxera was found among the vines as far as Malmesbury, he began searching for a way to combat the disease. It took several years to find a solution to this problem. It required grafting European vines onto the rootstock of American plants that were resistant to the disease. While some farms survived, it took several years to procure enough rootstock and many vineyards never recovered.

Image: Grape Phylloxera disease

Some scholars argue this destruction was a blessing in disguise. It lowered supply and increased the profits of the remaining farmers. It also led to some crop diversification and further brandy production improvements. Despite the collapse of the market and a crippling disease, the South African wine industry would face further challenges. In the late 19th and early 20th century, war broke out between the Cape Colony and the two Boer Republics.

War Breaks Out

At the beginning of the first Anglo-Boer war in 1880, the Boers led successful campaigns into Natal and the Cape. As a result, trade ceased entirely with the Boer republics. While the Cape was under siege, there were disruptions in shipping. Again, some scholars provide counterfactuals, claiming that the war increased wine prices. It is argued these higher prices provided a net benefit for the wine industry. However, given any possible and likely disruptions, this seems dubious.

The Second Anglo-Boer War ended in 1902. After both parties signed treaties, the Boer Republics were assimilated into the British Empire. The ensuing period should have resulted in some much-needed stability for Cape winemakers. Unfortunately, it had the opposite effect.

Overproduction led to price collapses which occurred alongside a twilight of international interest. This led to a period of malaise amongst Cape winemakers. It wasn’t until Charles Kohler and the founding of the Ko-operatieve Wijnbouwers Vereniging van Zuid-Afrika Beperkt (KWV) in 1918 that the industry would enjoy another period of sustainable growth and economic success.

KWV and South African Wine 1918-1994

KWV was responsible for a host of changes in the vineyard, the public eye, and on the floor of parliament during their tenure as the regulatory body. They introduced price floors, lobbied for protections, and united farmers. However, KWV has been criticised for lowering the quality of South African wine. With KWV incentivising yield over excellence, quality became secondary. They regulated the import and export of all alcohol, purportedly to protect the industry.

Real changes began when Professor Perold joined the KWV in 1928. KWV began to develop and research scientific methods to improve alcohol quality. To achieve this goal, they encouraged experiments with a host of new cultivars. By 1949 the world-renowned Roodeberg launched and developed a near-mythic status among oenophiles.

KWV continued to iterate both wines and regulations. These iterations looked to stimulate economic growth and the peripheral wine industries. Part of this was due to international sanctions during Apartheid. Part of it was to provide stability to an industry that seemed to encounter roadblocks every second generation. However, after the end of minority rule, KWV became a producer instead of a regulator.

Democracy, International Indifference, and Innovation 1995-Present

The Cape wine industry had survived the international Apartheid sanctions. This survival was much in part due to KWV’s interventions. However, the appeal for South African wines internationally had all but died. Few producers knew how to circumvent sanctions. Even fewer markets were interested in South African wines.

At the end of Apartheid, international trade sanctions were lifted. Several South African producers then attempted to sell their wines internationally. Rueda Wine Co sat down with Ian Naude, one of the first South Africans to spearhead wine exportation post-apartheid.

According to Ian, in the late 90s and early 2000s, London was the centre of wine. All the taste-makers and critics who shaped global wine culture resided in London. While it’s still the case today, succeeding in London was essential for a wine to be taken seriously. If Ian wanted to be successful, he needed to sell his wines in London.

According to Ian in the 90s, “There were a bunch of independent, really good wine shops in England, and we’d ask: ‘Do you have South African wines?’ and they’d say: ‘Yes, here, right at the back, is a bottle of this undrinkable Sauvignon Blanc. But it’s dusty in the corner in the bottom.”

Because of South Africa’s status as a bulk producer of grapes, it struggled to articulate itself as a wine producer of nuance. Additionally, Ian notes that most of the buyers were prescribed specific briefs as to what to buy.

“England was sending out their wine buyers to South Africa. They’d come out and ask for someone to make something like a New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc. And it happened with Australian Shiraz and American Chardonnay. And we’d ask: ‘Why do you want that? Do you know which continent you’re on?’ They’d respond that they had a mandate from the big retailers to get something trendy but cheaper. Because that’s what sells.”

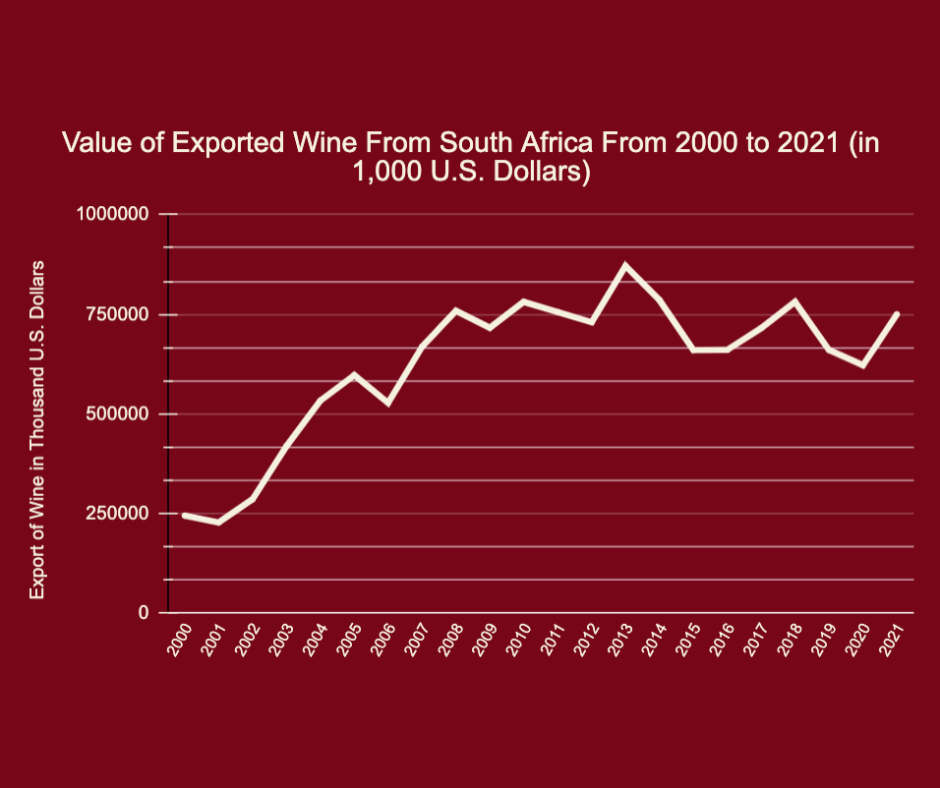

It took north of a decade of continuous effort at wine shows, shops, and tastings. Eventually, Ian and other dedicated wine producers forged a pathway for their wines in the international market. Ian credits the success of South African wine exports to international expat communities. Living in the United Kingdom and other countries, these communities created a demand for South African wine. Another reason for South Africa’s success in the wine market is its quality-to-cost ratio. The price-competitive South African wines are considered among the best in the world.

Image: Value of Exported Wine From South Africa From 2000 to 2021 (in 1,000 U.S. Dollars), published by Natalie Cowling, December 2023

A View to the Future

In wine, as in technology and science, more people are working on problems and innovation than ever before. The pace of advancement in methods and variety is breathtaking. This means new wines and different wines are coming to market faster than ever before. The next generation of South African wine producers is leading the charge of innovation. The younger generation is pushing the boundaries, testing varietals, techniques, and vogues. Like the Modernists in Barolo in the 1980s and 90s, there is a new cohort hungry for innovation and willing to experiment boldly.

Ian had a final thought to say on South African wine: “South Africa is known for exciting wines, with the best quality at a great price point. We’ve won Chardonnay trophies and sustainability trophies at the International Wine Challenge – one of the most prestigious award shows. When is it going to stop? It’s not. We’ve got this new generation coming up, and they’re going to keep innovating.”

And yet, not everyone is taking notice of South African wines. Caitlin Miller discusses the lack of attention given to South African wines by American consumers. It might still be some time before South African wines dominate these new markets. However, the growing international significance and relevance of these wines is undeniable. South Africa’s reputation as a wine hub and its influence seems to be on an almost parabolic trajectory. It is now commonplace to find South African wine producers in the top wine shops around the world. South Africa has become a host to many international winemakers looking to expand their skills. Furthermore, the list of international accolades awarded to South African wine producers is only growing. Wherever you look, you will find strong evidence for the industry’s optimism.

Written By: Rhett Sinnema

Fact Checked By: Fernando Rueda

Edited By: Fernando Rueda