Barolo, Italy: Wine is Art, Wine is Culture, Wine is History

The Alps nearly encircle the picturesque Piedmont region in north-western Italy. World-renowned for skiing, gastronomy, and leisure, this Italian region is home to storied wines. The Barolo and the Barbaresco regions are widely considered to produce some of the best red wine in the world.

At first glance, the greater Piedmont region doesn’t enjoy the languid summers and breezy winters of a typical winemaker’s paradise. The region suffers extreme temperature swings between the seasons. Violent summer rainstorms and predictable winter snowfall would see most regional wine producers farming Chardonnay or Pinot Noir grapes that typically ripen quickly.

And yet, in the south of the Cuneo province of Italy, we find an area that’s cold but not too damp in winter and almost perpetually sunny year-round. It is the surprising home of not only one of the most famous wine regions but perhaps the most difficult grape, Nebbiolo. Barolo and the greater Langhe are home to several world-famous Vinters. The eleven villages of Barolo, as well as Barbaresco and Nieve, are a UNESCO World Heritage site in north-western Italy.

But the 2014 UNESCO accolade merely confirms something known by the greater wine world for years. Barolo wines are world-class. Why else would Barolo earn the epithet of the king of the wines and the wine of kings? And like all monarchs, there is conflict in its history. But first, why does it deserve the crown?

Nebbiolo Grapes: A Delicacy of Dichotomy

The Nebbiolo grape, found in Barolo and the surrounding farms in the Cuneo province, is veiled in a greyish-purple or textured blue skin. Classed as a “noir” colour, it is famously difficult to farm and process. Piedmont was considered a great wine region even in Roman times, with vine pollen dating from the 5th Century BC. However, Nebbiolo’s first official records appear in the 1300s. The Nebbiolo grape takes its name from the Latin “nebbia”, meaning fog which refers to the fog surrounding the hills in October signifying the end of harvest.

Video: Drone footage by Marco Cane (@marcomalicane on Instagram) of the Piedmont region in late October illustrating the fog.

All Barolo producers are unified in their agreement regarding the expressiveness of the Nebbiolo grape. Two farms beside one another can have wildly different nuances in their wine. Even with similar cultivation techniques. This is due to the fussy nature of Nebbiolo which can highlight even the slightest differences in soil and typography. However, making the best red wine was never going to be a simple process.

Nebbiolo is a varietal that takes extremely long to ripen even though it begins to bud quite early in the season. The vineyard slope is an important growing factor, with preference given to south and west-facing slopes for their longer time in the sun.

The preferred taste profile of the ideal Barolo is generally each drinker’s discretion, especially with such an expressive grape. However, one can generally expect red rose, cherries, violet and spices with oak-enhancing notes of truffle, chocolate, leather and tobacco. Today’s Barolo is a dry style, with prevalent tannins, high alcohol, and a balancing, clarifying acidity. As consumers, techniques, and terroir change over time, so too can this preferred taste of the ideal Barolo.

In fact, most vintners before the first Barolo wine revolution primarily made sweet wines. Like much of Europe, these vineyards focused on farming grapes that ripened quickly. The early 1800s saw the production of the first dry Nebbiolo wine, during a greater European wine revolution. During this time, French techniques became popular throughout many regional Italian vineyards. These techniques allowed the fermentation process to leave little residual sugar, and a dry wine resulted.

The Nebbiolo grape poses other challenges besides a long ripening period. Producers in Barolo noticed the high acidity and the tannins, which posed a problem to the consumer’s palate. How could one make a wine that wasn’t bitter or harsh?

But, just because something is difficult, doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

And really, what does one expect of the progenitor of a monarch draped in purple? To ripen on command? To be easy on the palate immediately?

The Traditional Techniques: Maceration, Ageing and Barrels

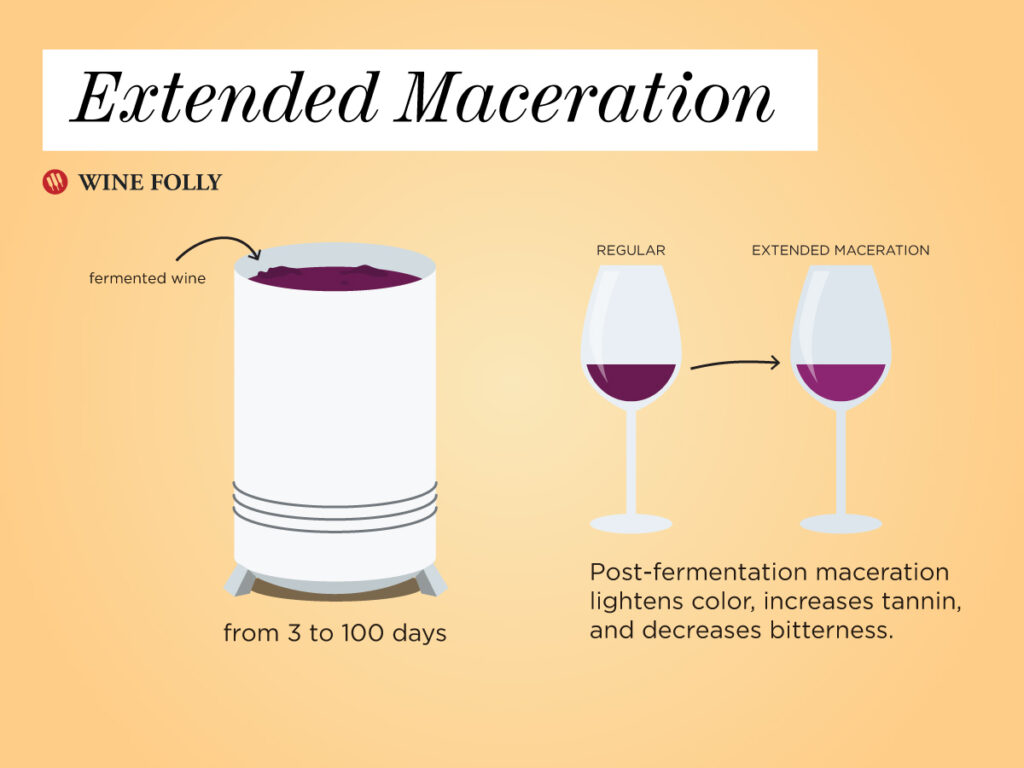

Maceration in winemaking is the process of soaking grape matter where the skin and stem are in contact with the juice. This allows for the impartation of colour, tannins, flavours and aromas into the wine’s juice. The Nebbiolo grape ripens late into a cold season. This forced the Traditionalist Barolo winemaker to macerate for a prolonged period. This drastically increased the tannins, which usually resulted in longer ageing times in oak to balance the tannins and acids properly.

The DOCG has minimum requirements for ageing. A Barolo requires at least 38 months of ageing in total, with DOCG rules stipulating at least 18 months in barrels made from oak or chestnut. To qualify as a Barolo Riserva, the wine needs to spend a minimum of 5 years in the cellar. They age in very large oak barrels of thousands of litres called botti. Such sizable barrels mean very little of the wine is in contact with the wood vessel. T This means that the flavours and characteristics of barrels affect the wine more gradually.

Larger barrels can pose another problem in the form of oxidization that is slower than desired. This may result in more acetaldehyde. Generally, this imparts unwanted flavours and aromas that untreated can lead to a fault in the wine. Extended ageing of Barolo wine helps to balance the acidity and tannin contents within each barrel.

Image: Large botti in use in Palladino cellars

And yet, despite all the difficulty, the wine produced is nothing short of sublime. It is a loved wine, and its producers have defended their techniques for making the best red wine zealously.

Producers had been using these methods for almost 180 years to craft legendary Barolo wines. A group of winemakers, later dubbed the Modernists, started experimenting with new techniques in the 1970s. By the 1980s, these Modernists caused an uproar when they claimed their wines belonged in the Barolo pantheon.

Both sides of the Barolo Wars have been widely covered. Some have argued that the Traditionalists were stuck in their ways, others that they didn’t want the competition, or that they feared what it would do to the appellation. Indeed, Traditionalists didn’t want to change techniques, but why would they? They were producing a superlative wine in a generationally established and honed method.

If you would like to experience great examples of producers who have both historically, and still to this day, adhered to the traditionalist methods you might enjoy the creations of:

- Francesco Rinaldi

- Giacomo Borgogno

- Diego Conterno

- Palladino

- Bruno Giacosa

- Alberto Burzi

- Ca’ di Press

- Bruna Grimaldi

- Elvio Cogno

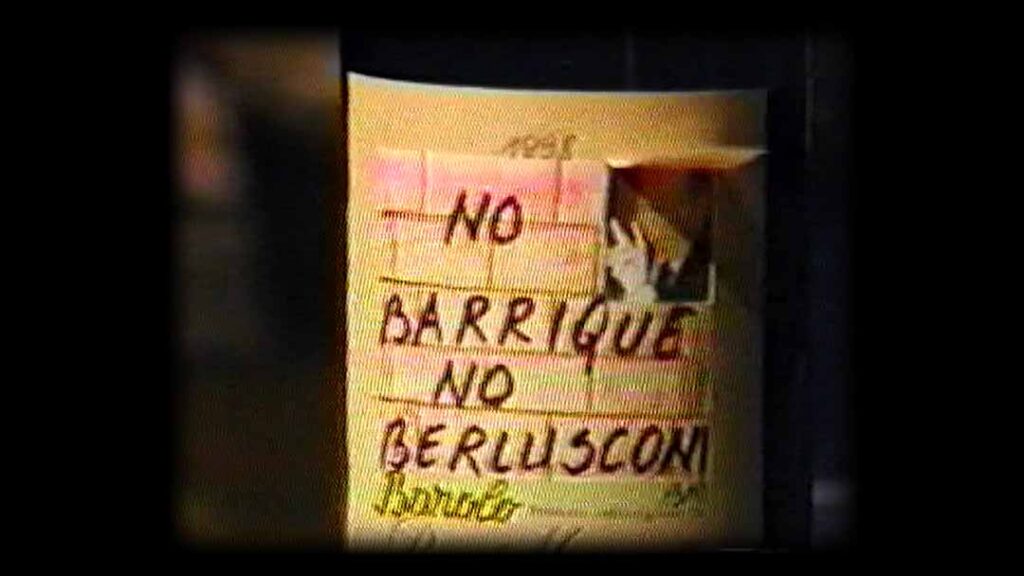

Image: A well-known bottle of Barolo wine produced by Bartolo Mascarello, proudly protesting against the use of the new barriques in the winemaking methods of the Modernists.

So, who were these Modernists, and what were they trying to change?

The Modernists: Advanced Techniques, an Elevated Wine?

A new trend began to emerge and gather momentum among wine consumers in the 1970s. More consumers began to opt for wines that were ready to drink over wines that required cellaring and ageing. Some Modernists feared that Barolo would be left behind if the median wine produced in the region required a decade (sometimes even 25 or 50 years) to reach optimal drinking conditions.

For many Barolo wines, cellaring for a minimum period of around 10 years might be encouraged to let the wine truly develop. That is not to say one can’t enjoy a young Barolo. However, the Modernist winemakers viewed the burdensome process as outdated with room for innovation. These winemakers started looking beyond the Barolo region to consider what other producers were doing better, and what modern technologies were at hand to help.

A Background on the Battle

During the 1970s Barolo wines were also relatively unknown in the international market. The farmers who worked the fields and grew the grapes would often sell the grapes to other winemakers. This was something the next generation of winemakers were desperate to change

In the late 1970s wine producer, Angelo Gaja began looking for ways to innovate the Barolo ageing process. Gaja commissioned and tested his own 225L toasted oak barriques which saw their first vintage released with much acclaim in 1978. Contemporaneously, the young son of a winemaker by the name of Elio Altare, began to battle with the traditional methods of farming his father used. These methods, which used harsh chemicals, had left the vines yellow and the soil damaged.

Altare was determined to enact change. In a famous moment of passion, Elio purchased a chainsaw and decimated the fruit and chestnut trees impacted by the chemicals, before turning his chainsaw to his father’s large botti. The Barolo Wars were now truly underway. Altare budgeted a trip to Burgundy in his Fiat 500 which he slept in. Here he saw new methods, modern machines, and bunch thinning on the vines. Altare was irrevocably influenced by the efficacy of the winemaking methods deployed in Burgundy during this period.

The Barolo Boys (which included Chiara Boschis and Domenico Clerico) were formed shortly afterwards. This group of young and passionate winemakers would gather weekly to blind taste and compare Barolo wines to the best they could afford. These comparisons left the winemakers believing that Barolo had clear and untapped potential. Slowly, they started implementing new methods that would shake the 1980s world of wine.

Image: Cellars of E. Pira Chiara Boschis, where barriques are used.

Understanding the Division

Given Barolos’ pedigree, it is no wonder there was bad blood when the Modernists tried to revolutionise the production techniques in the 1980s. Accused of besmirching the good name of Barolo wines and desecrating the grapes, Modernists were decried. There are even accounts of priests being called upon to bring an end to sacrilegious practices like green harvesting. But what exactly did they do to earn the ire of the Traditionalists?

The first contentious point of difference between the Modernist and Traditionalist approaches was their attitudes to maceration. Modernists steeped the grapes at lower temperatures to extract more colour and prevent fermentation from occurring. This is often called a cold soak or pre-maceration. This process holds the crushed grape slightly above freezing (at 5 degrees Celcius) for hours or even several days. The cold temperature prevents bacterial growth, while the maceration chamber is often pumped with other gases to prevent oxidisation. This allows for a gentler extraction before fermentation occurs.

After the cold soak and fermentation, the wines continue to macerate. This results in a small loss of colour but continues the process of releasing tannins, which carries with it the requirement of longer ageing to make the wine more palatable. Modernists gradually remove seeds and other grape matter to combat this, smoothing the tannin content. Lower tannins mean the wines do not have the same ageing obligation as traditionally produced Barolos and are ready to be drunk sooner.

Image: A closer look at the maceration process – Wine Folly

The Barrels of Barolo

Next, the Modernists used smaller toasted French oak barriques to impart more flavour and greater oxidisation from the ageing vessels.

These techniques allowed a similar flavour profile with a shorter ageing time. Additionally, Modernists began to use machinery like roto-fermenters and larger maceration chambers. As Barolo is a designated wine like a Burgundy Grand Cru, one can understand why Traditionalists would be up in arms about Modernists calling their wines Barolos.

But were these idealistic and innovative winemakers really being insolent and contravening the codified methods? One must remember that the Nebbiolo grape creates conditions of high tannin and acidity levels using the traditional method. The Modernists didn’t believe they were assailing the principles of Barolo winemaking. They were simply looking at the challenge of the Nebbiolo differently.

Why not leverage a smaller barrel to enhance specific flavour notes? Why not provide a wine that was more accessible and didn’t necessitate onerous ageing?

Using smaller casks, the Modernists ameliorated some of the oxidisation problems Tradionalists faced. More modern equipment resulted in cleaner processes and working environments. Earlier bottling and bottle ageing also allowed Modernists to leverage their cellar space more effectively. However, these small gains meant that Modernists were able to make Barolo more accessible to the world and reach new drinkers in new markets.

Some of the producers in the RWC portfolio who played an active role in the formation of the Barolo Boys or have previously used more Modernist techniques include:

Image: Reproduced with the permission of Chiara Boschis. Pictured above one can see Marc de Grazia (far right), next to Elio Altare, standing alongside Chiara Boschis, with Luciana Sandrone (far left).

The Battle for the Best Red Wine

On one hand, Traditionalists argued that these were generationally developed methods and processes that turned a difficult grape into a symphony on the tongue. To Traditionalists, Barolo wines are deserving of their title not just for the region from which they come but because the name was synonymous with the ardent, zealous, and laborious production process. A process the Modernists believe they are improving and had the effect of bringing the wine to more people. What’s to stop a Modernist from dubbing their wines a Barolo if all the necessary conditions of the region are met?

Regardless of where you fall in the debate, the conflict was instrumental in changing the face of Barolo producers. Since the 1980s, winemaking techniques and the greater process have received more care. Modernists have advocated for sustainability with a focus on fusing conventional, modern, and organic agricultural methods. Revolutions in the growing procedure have resulted in shorter ripening times for the Nebbiolo.

While the flame of the conflict burned brightly years ago, even this has waned with time. ‘Traditional or modern does not exist anymore…the new generation takes for granted those practices introduced and considered “modern” long ago”’, notes Chiara Boschis in an interview with Josh Dunning from Word on the Grapevine.

The process of winemaking has become more consultative in the Langhe, with winemakers sharing knowledge and experience to help elevate the wines. Modernists and Traditionalists ultimately have the same goal, even if they approach it from different positions. Everyone wants the wines of Barolo wines to continue their ascension. The region is undoubtedly greater by the refinement of processes, both traditional and modern.

Regardless of which methodology one thinks best, one thing is not at odds. Barolo wines are some of the best red wines in the world and are highly deserving of their status. The Wine of Kings comes from an explosive, expressive grape, worked by fanatical artists who see their work as a higher calling connecting them to the land, their culture, and their history.

This is a wine you want to know. This is its history. A wine you need in your cellar.

Written By: Rhett Sinnema

Edited By: Fernando Rueda